Last time, on Ayn Rand rationalizes selfishness….

Last time, on Ayn Rand rationalizes selfishness….

Sorry, I’m apparently working on a TV series here. I cannot confirm or deny whether it will air on Fox News.

In part 2, we addressed Ayn Rand’s argument that reason is important as a means to realizing our capability for pleasure, life, and giving to charity. OK, maybe not that last one.

Today, we continue with Rand’s essay, picking up with the theme that human life is the standard of value.

The Objectivist ethics holds man’s life as the standard of value—and his own life as the ethical purpose of every individual man.

In this case, the repetitive nature of this essay is helpful is useful to us, because it acts like a scene from the previous episode, in case you missed it. Rand either assumes that her readers have the attention span of a goldfish, or she just never edited her essays very well.

This repetitiveness, along with her stark dichotomies, straw men, and logical fallacies are trademarks of her writing. It makes good speeches for people prone to agree with her, and I can imagine many Objectivists feeling the emotional rhythm of the repetitive nature of these essays, coming at them in waves of freedom, individual virtue, and life, but this is nothing more than affective rhetoric. It’s no different from a good sermon or political speech, but it’s not good philosophy.

The rest of the essay is better imagined as a stump speech at a political rally, or perhaps a sermon at a revival. A godless, selfish, pleasure-seeking revival.

Rand has laid out the groundwork of her ideas and has tantalized us enough that it’s time to get to the flesh of the ideas. As the following commences, you might imagine the crowd becoming more animated, and perhaps hands pound lecterns with each emphasized word.

The three cardinal values of the Objectivist ethics—the three values which, together, are the means to and the realization of one’s ultimate value, one’s own life—are: Reason, Purpose, Self-Esteem, with their three corresponding virtues: Rationality, Productiveness, Pride.

Aren’t those things nice? I mean, sure they are! I like when I’m reasonable, I like when I have a purpose, and self-esteem is s good thing for all of us to have. The ability to be rational, production, and proud of my achievements are all good things. So, what’s my problem? Why and I not excited about this Ethic which promises me all of this? How could a rational person disagree?

Aren’t those things nice? I mean, sure they are! I like when I’m reasonable, I like when I have a purpose, and self-esteem is s good thing for all of us to have. The ability to be rational, production, and proud of my achievements are all good things. So, what’s my problem? Why and I not excited about this Ethic which promises me all of this? How could a rational person disagree?

Here’s the rhythmic, pulsating, cheer-inducing climax (although the end would be cut out in today’s political atmosphere);

It means one’s acceptance of the responsibility of forming one’s own judgments and of living by the work of one’s own mind (which is the virtue of Independence). It means that one must never sacrifice one’s convictions to the opinions or wishes of others (which is the virtue of Integrity)—that one must never attempt to fake reality in any manner (which is the virtue of Honesty)—that one must never seek or grant the unearned and undeserved, neither in matter nor in spirit (which is the virtue of Justice). It means that one must never desire effects without causes, and that one must never enact a cause without assuming full responsibility for its effects—that one must never act like a zombie, i.e., without knowing one’s own purposes and motives—that one must never make any decisions, form any convictions or seek any values out of context, i.e., apart from or against the total, integrated sum of one’s knowledge—and, above all, that one must never seek to get away with contradictions. It means the rejection of any form of mysticism, i.e., any claim to some nonsensory, nonrational, nondefinable, supernatural source of knowledge. It means a commitment to reason, not in sporadic fits or on selected issues or in special emergencies, but as a permanent way of life.

[emphasis mine]

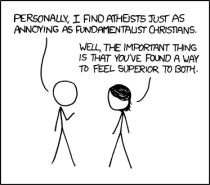

This is the kind of speech that would, for the most part, fit into an atheist convention. The values enumerated here are good ones, generally, and I agree with most of it. Where I start to differ is here:

It means that one must never sacrifice one’s convictions to the opinions or wishes of others (which is the virtue of Integrity)

I have a different use of ‘integrity,’ one which permits me to not hold onto my convictions so tightly. While I will not change my mind merely because others wish it, I would consider the wishes and opinions of others in the potential interest of changing my convictions if the evidence or perspectives warranted such a change. The level of stubbornness here is a little worrying, especially from a skeptical point of view (and no, I would not call Ayn Rand a skeptic). This rigidity of conviction is quasi-religious, yes, but it is also consistent with modern Right Wing politics where loyalty, conviction, and not hesitating or changing one’s mind are often considered virtues. I don’t think such things are necessarily virtuous.

Perhaps this level of conviction is related to “pride.”

The virtue of Pride can best be described by the term: “moral ambitiousness.” It means that one must earn the right to hold oneself as one’s own highest value by achieving one’s own moral perfection….by never placing any concern, wish, fear or mood of the moment above the reality of one’s own self-esteem. And, above all, it means one’s rejection of the role of a sacrificial animal, the rejection of any doctrine that preaches self-immolation as a moral virtue or duty.

Because nothing is more important than you. Your truth, your life, and your feeling of self-worth trumps everything. You (not humanity in general, just you) are the standard by which you decide which is right. And if anything out there conflicts with that self-esteem or value, then that thing brings with it death. In some ways, this is not all that different from the concept of “spiritual death” within some interpretations of Christianity; Any form of altruism is a kind of “sin” which separates you from true, selfish, morality.

Because nothing is more important than you. Your truth, your life, and your feeling of self-worth trumps everything. You (not humanity in general, just you) are the standard by which you decide which is right. And if anything out there conflicts with that self-esteem or value, then that thing brings with it death. In some ways, this is not all that different from the concept of “spiritual death” within some interpretations of Christianity; Any form of altruism is a kind of “sin” which separates you from true, selfish, morality.

I know this type of thought well. When I’m defensive, scared, and feeling insecure about myself. I paint myself into a corner with self-interest. And I can feel the rationalization churning away as I do this, because what’s happening when I feel this way is that I’m trying to hold back the flood-gates of things that contradict my own happiness, pleasure, and dissonance with the view of myself as a virtuous and good person.

What bothers me most is that while I get this, I know many other people do not get this, and many of them genuinely think that they are not insecure, defensive, or delusional about themselves. They just seem themselves as successful and awesome. You know, attributes consistent with narcissism.

I, therefore, think that I have the same gut feeling as Ayn Rand is describing here in her Ethic, and I recognize it for what it is; a self-centered and inconsiderate impulse–a reaction–against the threat of the Other. It is a reaction against being potentially wrong, of being uncertain, of having to admit that maybe other considerations besides my own might be worth caring about. It’s tempting, sometimes, to just go with what’s comfortable and easy; to allow my selfish impulses to rule my decisions, actions, and subsequent worldview created by trying to rein those actions into a coherent worldview of myself as virtuous and awesome.

Knowing and understanding other people is hard, and knowing what we want and what brings us pleasure is easier by comparison. The idea here seems to be that if we can see ourselves as virtuous, reasonable, and productive people then we can take pride in that. It’s not our job, says this Ethic, to account for the reasonableness, production, or pride of others. That’s their job. Anyone else who is not succeeding is doing so because they aren’t being reasonable or productive, and so their struggles are their own doing.

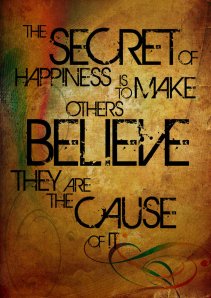

Happiness is the successful state of life, suffering is the warning signal of failure, of death.

That is simply not true. This is a wonderful example of the just-world fallacy at work. The world does not, whether by gods, fate, or karma, dish out happiness to the just or not suffering to the unjust. This delusional belief, which is similar to the ideas behind The Secret and similar worldviews, must be confronted and slapped down as the bullshit it is. And yet it is all too common a belief that if you work hard and are ethical (no matter the ethic), you will be rewarded. It’s quite possible you won’t be. It’s also possible that you will be very happy while making many people around you miserable. It happens all the time, and it blinds the happy person from the effects of their behavior. And if said person is predisposed to selfishness and egoism, they are even less-likely to realize it.

All too common.

More John Galt:

“Happiness is a state of non-contradictory joy—a joy without penalty or guilt, a joy that does not clash with any of your values and does not work for your own destruction. … Happiness is possible only to a rational man, the man who desires nothing but rational goals, seeks nothing but rational values and finds his joy in nothing but rational actions.”

Pure delusion. But at least Rand is aware enough to make the following distinction:

If you achieve that which is the good by a rational standard of value, it will necessarily make you happy; but that which makes you happy, by some undefined emotional standard, is not necessarily the good. To take “whatever makes one happy” as a guide to action means: to be guided by nothing but one’s emotional whims.

The distinction is important, and I’m glad she made it here, otherwise she leaves herself open to the “Nietzschean egoism” she despises. She’s not stupid; she’s just myopic, oblivious, and obtuse.

Further, she is no mere hedonist;

This is the fallacy inherent in hedonism—in any variant of ethical hedonism, personal or social, individual or collective. “Happiness” can properly be the purpose of ethics, but not the standard.

I’m also glad she makes this distinction as well, as it is also important. Happiness, Rand argues, is great as a result but it is not the standard. The standard is, of course, is life itself (according to Objectivism, anyway). A happy life is just the reward for living with reason, productivity, and pride. All bullshit, of course, but at least it’s somewhat internally coherent bullshit.

I’m also glad she makes this distinction as well, as it is also important. Happiness, Rand argues, is great as a result but it is not the standard. The standard is, of course, is life itself (according to Objectivism, anyway). A happy life is just the reward for living with reason, productivity, and pride. All bullshit, of course, but at least it’s somewhat internally coherent bullshit.

Perhaps the following is a more clear illustration of the relationship between sacrifice, conflict, and the difference between egoism and altruism. This quote comes directly after addressing utilitarianism, wherein (according to Rand) the centrality of desire leads to situations where “men have no choice but to hate, fear and fight one another, because their desires and their interests will necessarily clash.” Desire, says Rand, cannot be the ethical standard.

And if the frustration of any desire constitutes a sacrifice, then a man who owns an automobile and is robbed of it, is being sacrificed, but so is the man who wants or “aspires to” an automobile which the owner refuses to give him—and these two “sacrifices” have equal ethical status. If so, then man’s only choice is to rob or be robbed, to destroy or be destroyed, to sacrifice others to any desire of his own or to sacrifice himself to any desire of others; then man’s only ethical alternative is to be a sadist or a masochist.

The moral cannibalism of all hedonist and altruist doctrines lies in the premise that the happiness of one man necessitates the injury of another

OK, that’s interesting. The idea seems to be that built into the very fabric of altruistic ethical philosophy implies that all desires, whether of the owner or the robber, are indistinguishable, and so equally valid. As a result, Rand seems to argue, we are all in perpetual conflict and that only by inciting sacrifice can we avoid perpetuating this conflict.

If you believed in a Hobbesian universe where we were all brutes who will try to rob, cheat, and lie to each other for our own benefit (a quite cynical view), enforced altruism might seem a way to get society to work. But what if that was not the motivation for altruism? What if the reason we ask for consideration, compromise, etc are not because we assume humanity is in a perpetual state of conflict?

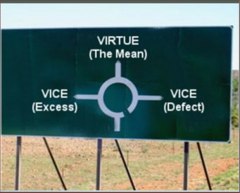

It’s very possible that a sense of empathy, altruism (in the sense of the willingness and ability to sacrifice some of our desires, not Rand’s caricature), and care can be mapped onto a reasonable and logical moral framework without appealing to this view that leads to either sadism or masochism. If that were true, then self-sacrifice would not be causally related to conflict, and so we would not have to demonize altruism. Then, if (like Rand) we were to believe that human interactions are not inherently conflict-based, the solution does not have to be a fundamentally selfish set of values and virtues, whether Objectivist or otherwise. The solution could also be altruism or some compromise between selfish and selfless values (as most ethical philosophy does).

It’s very possible that a sense of empathy, altruism (in the sense of the willingness and ability to sacrifice some of our desires, not Rand’s caricature), and care can be mapped onto a reasonable and logical moral framework without appealing to this view that leads to either sadism or masochism. If that were true, then self-sacrifice would not be causally related to conflict, and so we would not have to demonize altruism. Then, if (like Rand) we were to believe that human interactions are not inherently conflict-based, the solution does not have to be a fundamentally selfish set of values and virtues, whether Objectivist or otherwise. The solution could also be altruism or some compromise between selfish and selfless values (as most ethical philosophy does).

Choosing selfishness, whether as Rand does via reason, purpose, and self-esteem or otherwise, would then be as valid as any oither attempt to formalize ethics, rather than being objective or the true foundation of ethics, as Rand claims.

If our being reasonable, productive, and proud lead to us being happy (because we deserve it), then why she even worried about whether we are altruistic? Or, is it that her Ethic rids the world of this conflict and the injury. Or perhaps it just ignores it by eliminating selfless acts? If conflict is not inherent to human interaction, then being altruistic is not necessarily self-immolating, and will not lead to any kind of death. It might be unnecessary, but that’s another question than it being evil. I’m having trouble making sense of all that. So much for internal coherence, I suppose.

In any case, let’s see how Rand deals with some of the implications of being selfish on other people.

[W]hen one speaks of man’s right to exist for his own sake, for his own rational self-interest, most people assume automatically that this means his right to sacrifice others. Such an assumption is a confession of their own belief that to injure, enslave, rob or murder others is in man’s self-interest.

This is obviously a preemption of concerns about Rand’s Ethics implying that since we shouldn’t sacrifice ourselves, it means we simply sacrifice others. It seems to imply that by doing neither type of sacrifice (of ourselves or others), we are left with neutral parties free to interact without a sense of sacrifice or conflict between them. Nobody has to sacrifice anything! Sounds great.

But what if the very nature of refusing to give an inch of your interests (or convictions) was inherently sacrificial of not only the interests of others, but ultimately our own interests? Not because the others are moochers or trying to steal from us, but because the very nature of human interaction or communication is already inefficient and requires some level of effort (on both parts) in order to succeed. The very nature of communication, therefore, would require self-sacrifice.

Let me try to sketch this out.

Communication is inherently difficult, but even more so the more different we are. If I am to interact with other people, especially if those people are significantly different from me (whether due to language barriers, psychological differences, temperaments, etc), then that interaction inherently requires some level of work on my part to effectively communicate my proposals, ideas, etc. So, is this work in my interest? Not always.

Communication is inherently difficult, but even more so the more different we are. If I am to interact with other people, especially if those people are significantly different from me (whether due to language barriers, psychological differences, temperaments, etc), then that interaction inherently requires some level of work on my part to effectively communicate my proposals, ideas, etc. So, is this work in my interest? Not always.

When misunderstandings or conflicts do occur (and they will, even among Objectivists), the unwillingness to give up any level of self-interest for the sake of another will make it very difficult, if not impossible, to communicate the specifics of a neutral and mutually beneficial proposal, let alone where there actually is a conflict of interests.

This unwillingness blocks the possibility of understanding points of view not immediately in the Objectivist’s interest, or even ones that might be in their interest but are unknown to them. But because an Objectivist would be unwilling to extend any “altruistic” effort to understand the interests of other people, they would never learn about the ideas connected to those alien interests. What’s worse is that they might not even see this as a loss. Nothing in The Objectivist Ethics would imply otherwise.

If sacrifice for the sake of others is actually evil, then perhaps understanding others might require being evil in some cases. My taking the time to try to empathize, listen, and hopefully understand the interests of others is a sacrifice on my part. It’s a sacrifice of my time, patience, and cognitive effort to communicate with people who think differently than I. And if I see this effort as a sacrifice, then Rand might say that putting forth that effort would be bowing to altruistic demands, and therefore not being virtuous. And the result of this is that I cut myself off from not only potential neutral trade partners, but sets of ideas which are significantly different from my own, which will end up isolating myself from people with diverse perspectives, opinions, and worldviews.

Just like with Galt’s Gulch, Objectivism seems to want to isolate itself from the world, effectively impoverishing its access to ideas, people, and experiences which they might learn from if they were not so self-absorbed and against any sort of self-sacrifice.

Just like with Galt’s Gulch, Objectivism seems to want to isolate itself from the world, effectively impoverishing its access to ideas, people, and experiences which they might learn from if they were not so self-absorbed and against any sort of self-sacrifice.

Getting back to Rand’s argument, Rand is asserting that the non-selfish ethical systems (whether utilitarian, Kantian, or full-blown altruism) view the world as full of people ready to take advantage of others and to ask us to sacrifice ourselves as a reaction to that inherent conflict. Rand does not assume this conflict is necessarily the case but neither do I, who she would have called an altruist, think that this is the case (no, I’m not even that cynical).

Let’s continue with the essay.

The idea that man’s self-interest can be served only by a non-sacrificial relationship with others has never occurred to those humanitarian apostles of unselfishness, who proclaim their desire to achieve the brotherhood of men.

Perhaps it has not occurred to some, but it has occurred to me, at least. Ayn Rand has set herself up as a sort-of prophet for true ethics, but what she really is doing is demonstrating her ignorance and misunderstanding of ethical philosophy in such spectacular fashion that all I can to is stare, slack-jawed. And yet this philosophy is revered by so many people!

The great speech of the essay has climaxed, and we head towards resolution. At this point, we’re past the part of the great speech where the music swells and the lights flicker, and we reach the part where the crowd is hushed and the speaker drops into a lower register, almost whispering so the everyone needs to strain to hear them. It’s now time for Objectivist pillow-talk.

The Objectivist ethics proudly advocates and upholds rational selfishness—which means: the values required for man’s survival qua man—which means: the values required for human survival—not the values produced by the desires, the emotions, the “aspirations,” the feelings, the whims….

The Objectivist ethics holds that human good does not require human sacrifices and cannot be achieved by the sacrifice of anyone to anyone. It holds that the rational interests of men do not clash—that there is no conflict of interests among men who do not desire the unearned, who do not make sacrifices nor accept them, who deal with one another as traders, giving value for value.

Nobody expects, accepts, or offers any compromise. This neutrality is a sort of marketplace of self-interested people who will trade their ideas and products in order to create a non-competitive world, or so Rand thinks. Not competition. Not brutish, emotional, covetous desire.

However, when this Objectivism is actually put into practice in life with other people around, it does in fact create a kind of conflict. The conflict is there, it’s just that this philosophy encourages people to re-define any sign of this conflict as an attempt of moochers and robbers to steal from them in some way, rather than some actual injustice.

Any request or expectation of consideration looks like a demand for the Objectivist to sacrifice their convictions; to give into altruistic morality. Any request of empathy is a demand for the Objectivist or egoist to sacrifice themselves in some way; a demand to give up what they consider to be virtues. Why should they give up anything, material or conceptual, for your sake? You should do that yourself (they think as they step on your toes, dominate a conversation, or otherwise impose themselves onto the world around them). The logical conclusion of this view of self-sacrifice makes any request of empathy or consideration look like a kind of demand or theft.

In order to operate effectively in the world, however, consideration, empathy, and some level of self-sacrifice is necessary; not merely ethically, but practically as well. Until we are able to transcend the realm of individual interests and dive into intersubjective concerns (where ethics lives), we can’t even consider what I want from, to do, etc other people. In other words, it’s not even possible to have interests related to others until I have some ethically relevant relationship with another person. I can only do this by sacrificing my immediate interests for the sake of external reality.

But Objectivist Ethics never leaves the realm of individual interests, because it considers doing so “evil”. Now, actual Objectivists might employ some level of empathy and consideration in their lives, but this would accidental or incidental, rather than inherent to the Ethic. That is, if the Objectivist doesn’t have an inclination towards empathy or consideration already, Objectivism does not encourage this empathy (and actually discourages it), so the Objectivist can feel fine not employing such tools, isolating themselves from people, ideas, and whole sections of cultures.

Objectivism gives us no reason to employ empathy, and even uses reason to imply that being asked to do so is a form of theft. But without empathy of some kind, communication and understanding are not possible, leaving the non-empathetic Objectivist as indistinguishable from the “Nietzschean Egoist,” who merely does whatever they want. If Ayn Rand ever employed any kind of empathy, she was only doing so while being a bad Objectivist.

Rand’s claims that her Ethic does not lead to the sacrifice of others is not reasonable given that the unwillingness to empathize does not, in fact, create a neutral relationship. The difficulty of communication, understanding, etc create an imbalance; not one of tension between owner and potential robber, but simply of comprehension. Thus, it hurts us all. This is the absurdity of calling any self-sacrifice as evil; avoiding self-sacrifice hurts us all in the long run.

Rand continues:

Only a brute or an altruist would claim that the appreciation of another person’s virtues is an act of selflessness.

Also,

a trader is a man who does not seek to be loved for his weaknesses or flaws, only for his virtues, and who does not grant his love to the weaknesses or the flaws of others, only to their virtues.

In other words, we don’t love someone despite their flaws. We love them when they don’t have any, or at least we love them insofar as their virtues overshadow their flaws. That may sound good to you, but I would caution you against falling into a trap of privilege here; many of us struggle with aspects of ourselves that make our virtue harder to act on.

I’m not convinced that reason, productivity, and pride are sufficient to create a person of virtue. Is there no room for depression and its side-effects in virtue, where one might struggle with pride? What about economic factors that hold many people back from production? Are they not allowed to be loved or considered virtuous? What about a person whose reason is handicapped, at times or chronically,by either emotional disorders or simple cognitive inability? Do they get no love?

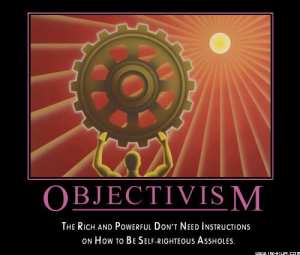

The worry here is that a person who wants to adopt this view will either be the type of person who is blind to their own faults (narcissists, for example) or who exist in such a bubble of privilege that they are deluded into thinking that they actually earned their success and happiness without the sacrifice of others around them. This view, therefore, is in tension with social justice insofar as economic and neuro-typical privilege (at least) is concerned. It seeks to pump up the already privileged, stigmatize the non-privileged, and to rationalize it all as “reasonable.”

The worry here is that a person who wants to adopt this view will either be the type of person who is blind to their own faults (narcissists, for example) or who exist in such a bubble of privilege that they are deluded into thinking that they actually earned their success and happiness without the sacrifice of others around them. This view, therefore, is in tension with social justice insofar as economic and neuro-typical privilege (at least) is concerned. It seeks to pump up the already privileged, stigmatize the non-privileged, and to rationalize it all as “reasonable.”

But the line between reason and whim, as I discussed previously, is but a neuron or two away and all too often we are incapable of distinguishing them, especially when privilege takes its toll on us. I do not believe that Ayn Rand, or her followers, are any more reasonable than utilitarians, Kantians, or even those who follow the ethics of care (for example). I think they think they’re more reasonable, but we have Dunning-Kruger for that. But, of course, knowing you are subject to the Dunning-Kruger effect requires a certain level of self-awareness, attention, and care towards others. People prone to follow Ayn Rand have little of those qualities, in my experience.

And yet, they speak of love, human society, and the trade of knowledge and potential. However, Rand speaks of these things as things to be earned solely, and those “moochers” and other parasites cannot live in a rational, loving, cooperating society. It all sounds great, especially to Objectivist ears, but it’s an ideology which is startlingly ignorant of the nature of knowledge, intelligence, and the complexities of power and privilege.

But, what of government?

The only proper, moral purpose of a government is to protect man’s rights, which means: to protect him from physical violence—to protect his right to his own life, to his own liberty, to his own property and to the pursuit of his own happiness. Without property rights, no other rights are possible.

And while Rand does not deal with the politics of Objectivism here (the answer is Capitalism; “full, pure, uncontrolled, unregulated laissez-faire capitalism”), I’m glad she’s for the separation of church and state, at least.

In a sort of summation, she offers this:

I have presented the barest essentials of my system, but they are sufficient to indicate in what manner the Objectivist ethics is the morality of life—as against the three major schools of ethical theory, the mystic, the social, the subjective, which have brought the world to its present state and which represent the morality of death.

And then, following some more analysis of each school of ethical theory, she says that

It is not men’s immorality that is responsible for the collapse now threatening to destroy the civilized world, but the kind of moralities men have been asked to practice.

And then she ends by quoting John Galt (AKA herself) once more.

“You have been using fear as your weapon and have been bringing death to man as his punishment for rejecting your morality. We offer him life as his reward for accepting ours.”

However, the life that is offered is one infested with myopia, privilege, and an impoverishment of understanding of anything not immediately self-interested. This is a philosophy not built upon reason, but of rationalized selfish whims.

Smart people are really good at rationalizing their whims and making themselves think they are being reasonable. Ayn Rand was a smart woman who found a way to not only do so for herself, but created a worldview that still resonates with millions of people. If you look for them, you will find real places called Galt’s Gulch, and the influence of some of Rand’s ideas are still quite popular in political spheres, specifically for Rand Paul and many others within the Tea Party.

Smart people are really good at rationalizing their whims and making themselves think they are being reasonable. Ayn Rand was a smart woman who found a way to not only do so for herself, but created a worldview that still resonates with millions of people. If you look for them, you will find real places called Galt’s Gulch, and the influence of some of Rand’s ideas are still quite popular in political spheres, specifically for Rand Paul and many others within the Tea Party.

This essay demonstrates a sophomoric ethical philosophy, hardly worth serious attention except for its continuing influence. But there is more book to go (18 chapters, in fact), so we still have a way to go. Future posts will be shorter, as I will try not to address the same points.

I might need a day or two to recover, however.