Many years ago I read Ayn Rand’s novel Atlas Shrugged. I found it entertaining, but mostly it was preachy. The convoluted universe within contains idealistic characters who give long diatribes composed in an attempt to get the reader riled up about how our culture is broken morally, and how we can pull ourselves up through our individual greatness to a utopian future. Such narratives failed to evoke more than mild positive feelings in me, and in the end I found Ayn Rand’s novel to be emotionally immature and philosophically problematic.

And yet, in opening her essay about ethics, Ayn Rand quotes one of the characters from this book as a representative of her “Objectivist Ethics,” as a man we should try to emulate. Here are the words of John Galt.

“Through centuries of scourges and disasters, brought about by your code of morality, you have cried that your code had been broken, that the scourges were punishment for breaking it, that men were too weak and too selfish to spill all the blood it required. You damned man, you damned existence, you damned this earth, but never dared to question your code. …

…

“Yes, this is an age of moral crisis. … Your moral code has reached its climax, the blind alley at the end of its course. And if you wish to go on living, what you now need is not to return to morality … but to discover it.”

And with this as the battle cry, Ayn Rand attempts to help us discover ethics, a process which seems to include trashing the history of ethical philosophy as misguided and ultimately evil. Despite her antipathy to Nietzsche’s egoism, this is very much a quest that we have found Nietzsche to be on many years before (especially with Beyond Good and Evil), and while I appreciate the need for a re-valuation of value (Nietzsche’s phrasing), as we have seen previously I am skeptical that Ayn Rand’s contribution is worthy of significant seriousness. So, in order to understand why, let’s take a look at a few highlights from chapter one of The Virtue of Selfishness, which is composed of an essay called “The Objectivist Ethics.”

—

What is morality/ethics?

It is a code of values to guide man’s choices and actions—the choices and actions that determine the purpose and the

course of his life. Ethics, as a science, deals with discovering and defining such a code.…

The first question is: Does man need values at all—and why?

These are fair questions and definitions for starting to think about ethics. And I agree with Rand that ethics is essentially a scientific, or at least empirical, exercise. Rand is reacting, in part, to the movement in popular ethics which was largely subjective and relative, and while I am not a relativist myself I am also not an Objectivist. One thing to be aware of is the dichotomy set up there; those are not the only options.

Returning to the distinctions between reason and whims, which we looked at in the introduction, Rand asks the following.

Is ethics the province of whims: of personal emotions, social edicts and mystic revelations—or is it the province of reason? Is ethics a subjective luxury—or an objective necessity?

Clearly, Rand thinks that ethics is not a mystical, social, or subjectivist project. Rather, it is “scientific” and “objective”–hence Objectivism. And despite the fact that a number of philosophers, including Nietzsche, have sought a scientific approach to ethics prior to Rand (and many more since Rand wrote this book), Rand has the following criticism.

No philosopher has given a rational, objectively demonstrable, scientific answer to the question of why man needs a code of values. So long as that question remained unanswered, no rational, scientific, objective code of ethics could be discovered or defined.

The greatest of all philosophers, Aristotle, did not regard ethics as an exact science; he based his ethical

system on observations of what the noble and wise men of his time chose to do, leaving unanswered the questions of: why they chose to do it and why he evaluated them as noble and wise.

I’ve admired Aristotle’s approach to ethics for a long time. I don’t consider him to be the greatest philosopher, but I think his contribution to philosophy is profound and influential. His Nichomachean Ethics is among my favorite works of ethical philosophy, and anyone who takes ethics seriously should be at least familiar with it. Let’s spend a moment looking at Aristotle’s Virtue Ethics, since Rand at least hold Aristotle himself in high regard.

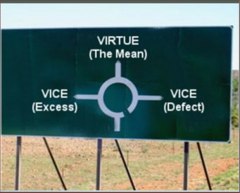

“Virtue Ethics,” as Aristotle’s view is called, is an interesting and powerful method for thinking about how we behave and why. Essentially, it focuses less on outcomes or principles, and instead looks at varying human attributes–virtues and vices–and considers what would be the ideal level of such attributes, which is often some moderate between extremes. We identify which temperaments make better people, and try to emulate those characteristics in ourselves. Looking at the individual behavior of a person who is admired, respected, and sought as virtuous is often an indicator of (at least) who a culture holds as a virtuous person.

However, if we left it there we would be missing something. Ethics, as I stated in the introduction, can start with individual interests, attributes, and concerns, but it must transcend these things to be powerful enough to be ethical. Much of Objectivism can be seen as a lesson in how to be an individual, but it often fails (for reasons I’ll get to) in addressing ethics primarily because it rejects the very definition of ethics. I realize Rand is doing this intentionally, I just think it fails.

Why? Let’s get back to Aristotle.

What does it matter what this or that “wise” or “virtuous” person does unless we are interested in the social and cultural implications of those actions? That is, unless we are concerned with the implications of a set of actions or virtues which we may or may not emulate, then why would we even bother paying attention to the actions of said person? Unless we are concerned with how our actions affect other people, or with how their actions affect us, then we would not care what they did. It is the very fact that we concern ourselves with the right set of actions and virtues in (other) people which excavates the fact that ethics is a social question, not an individual one.

Rand rejects “subjectivism,” but the “Objectivism” that she proposes rarely, if ever, leaves the bounds of individual interest. She thinks that the effect on the world will be one of love, collaboration, and fair trade (as we shall see), but she never articulates how this happens or why we should care about that. Without a connection between the virtues of selfishness and how it avoids making our culture and society sick, evil, or at least unsuccessful, we are left holding a bag of our own selfish interests and successes without any overt concern for anyone else, or even why we should care about them. Ayn Rand never traces how her virtues of selfishness translate into a better world in this essay, and often states directly that we should not be concerned with this. If this is not a contradiction, it is at least a serious tension.

Selfishness per se is insufficient to address a question of social significance, such as ethics. Selfishness cannot bring in empathy (a word that never comes into “The Objectivist Ethics” or the rest of the book) or understanding, which seems intentional on Rand’s part. Rand seeks to de-couple ethics from its mystical past of self-sacrifice and “irrationality” in an attempt to de-couple reason from emotion.

But you can’t de-couple reason from emotion. You can’t be coldly reasonable and rational without concern for emotion, because our brains simply are not constructed in such a way that we can separate reason from emotion. We can delude ourselves into thinking we have done so (which Rand seems guilty of), but this is an illusion.

Ayn Rand is just focusing on her set of preferences and turning them into “objective” ideals (they are, at best, intersubjective). There is nothing wrong with that inherently, but her conclusions are so self-centered, myopic, and (ironically) disjointed from reality that Objectivism can only appeal to those who are predisposed to avoiding any kind of self-sacrifice for the sake of their own selfish interests.

In other words, it seeks as a rationalized shelter for selfish people, rather than a reasonably constructed utopia of ethical living away from an evil world of altruistic fear.

Insofar as Western thought has tried to de-couple ethical philosophy from religion and mysticism specifically,

…their attempts consisted of trying to justify them on social grounds, merely substituting society for God.

This is quite similar to arguments I have heard from many conservatives, especially Christian apologists, who claim that liberals/atheists are substituting the government, science, or (in one case, at least) time for god. Society, progress, and time are all “replacements” for the missing god, supposedly. The basic complaint seems to be that where people try to understand something, all they end up doing is replacing god, rather than actually figure out what the truth is.

Now, Ayn Rand was no fan of god (she was an atheist and spoke against religion openly). Her complaint here is not that in creating a social morality we are replacing the true source of morality; god. Her problem seems to be that in attempting to re-think ethics as secular or social ideal, we are just doing the same thing as the broken systems of religion, communism, etc were doing, and which Objectivism is trying to transcend. I have had similar thoughts in relation to some of the humanist community, and so I recognize this complaint as sometimes legitimate.

Insofar as secular ethics merely clones religious ethics, I think this criticism is fair. But is this what ethical philosophy was doing? And even if it was then, is it still doing so now?

No.

If we are to build ethics from the ground up (using reason and science), it does not mean that the structure of social morality must be abandoned as a conclusion, even if we do abandon a subjectivist, social, or mystical grounding of ethics as a starting point. One can build a reasonable ethics that leads to us thinking about ethics as a social phenomenon without starting there. In fact I’d argue that not only must we start with the facts of individual interests and considerations, if we don’t arrive at a set of social considerations when we’re done then all we are doing is arguing for the abandonment of ethics in favor of individual interests, not the discovery of ethics.

How does Rand see the relationship between society and ethics?

This meant, in logic—and, today, in worldwide practice—that “society” stands above any principles of ethics, since it is the source, standard and criterion of ethics, since “the good” is whatever it wills, whatever it happens to assert as its own welfare and pleasure.

Rand’s confusion here is to say that, for the culture and society she is criticizing, ethics starts as being what society claims to be right, wrong, or true. This description of social ethics, if true, is indeed circular and does often lead to a kind of relativism rather than anything objective or true. But this description is a straw-man. What Rand continues to misunderstand is that it is possible (and has been done, many times) to build an ethical system from the ground up (using reason, and not mere “whims”) and conclude that ethics are about social good and may, in fact, include some aspects of altruistic thinking.

Rand is essentially saying that we have all been spoon-fed a social standard of morality which is harmful to us as individuals and as a group, and I’m responding by saying simply that this is not necessarily true. It might be true for some people; some people might accept a social morality without thinking about it or taking the time to care about their individual interests enough, but this does not imply that we must abandon social concerns as a legitimate question in ethics in order to be reasonable.

My argument is that ethics can start with individual virtues, selfish concerns, and other non-inherently social factors and when we then ask the question about interactions, differences of opinion, etc, then those individual factors coalesce and supervene to create a larger level of description via the emergent properties of selfish interests.

That larger level of description is ethical philosophy. In the same way that cells operate individually, yet when we study the implications of how they interact, new levels of description (tissues, organs, bodies, ect) come into view.

If Ayn Rand’s ethics were biology, it would imply that the only thing that would matter is how cells operate independently of other cells. And just like cellular biology isn’t all of biology, selfishness isn’t all of ethics. Selfishness is, at best, the start of the conversation. How does Ayn Rand deal with the rest? Well, we’ll have to see in part 2.

—

This is a good time to pause. In reading, analyzing, and writing this post I have managed to compose nearly 9000 words (so far), and after writing a nearly 6000 word introduction, I decided to break up this analysis into 3 parts. I will publish part 2 in the next day or so, depending on how busy I am.

All this philosophical blather is beside the point. People have psychopathic and empathic traits in varying amounts, and likely other traits and circumstances that make them more or less likely to care about the welfare of others. I would put the “objectivists” at the psychopathic end and the “knee jerk liberals” are at the empathetic end. The real fallacy is thinking there are rational arguments that might influence one camp to accept the values of the other.