Preface

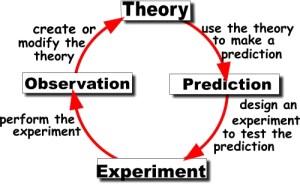

There is an idea in our culture, derived in part from the Enlightenment and many of its thinkers including many of those who helped form the United States, that the universe is fundamentally rational. The idea is that as we learn about the universe and how it works, the underlying assumption is that what we find to be true is both true in every circumstance (universalization, which is also relevant in Kant’s ethical principle) and coherent with the rest of what we find.

That is, the world is essentially connected and coherent. The basis for trusting in scientific methodologies as sensible predictions and descriptions of the nature of reality is based upon this view, because if this consistency was not true than using any description of the universe based upon any observation would be useless, since there would be no guarantee that another observation in another place or time would yield the same result.

As a side note, it has been pointed out many times that if such things as miracles, or more generally a supernatural realm or powers, were to be real then this would make this rationality of the universe meaningless, since at any given time a power, force, or being which is supernatural could simply dispense with that rationality and intervene essentially “magically.” It would make science useless because we could not hope to make sense out of a world that can act essentially randomly or at least without consistent actions leading to theories or laws.

But enough of the opaque philosophical preface, let’s get to what I want to talk about today.

Cooperation

Especially in the more liberal world in which i grew up, there is an ideal of cooperation and striving for practical compatibility which underlies much of our thinking. We want to get along with not only other people, but their ideas and dreams. We want our dreams to fit in with the dreams of our neighbors so that when we all dream together, it creates a jig-saw tapestry of diverse and intertwining beauty.

It is a wonderful and beautiful image, especially for this polyamorous man who seeks intertwining in many ways in my own life. It appeals to even me, the often-cynic and occasional (or not-so-occasional!) grump (or Grinch, as the time of this writing might imply) who is often found to be pointing out where things don’t seem to be cohering or cooperating nicely.

But is it true? I mean, of course t can sometimes be true (right?). I mean, at least under ideal circumstances people’s beliefs, desires, and ideals will match up quite nicely and they can get along just fine. And many people believe that if we were to be more tolerant and accepting of others’ ideas then we could all get along nicely.

And, to a certain extent this is true. If we were willing to accommodate more, to compromise more, and to tolerate more we could all fit our puzzle pieces together and create, well, some kind of image.

But would that image be meaningful? Would it be even internally consistent or coherent? Could it be a picture of reality?

Truth and fallacy

The problem is that the best way to find ways to co-exist peacefully with people of different ideals is to re-shape our own in order to fit wither theirs, so long as they are also doing the same thing. It may imply the occasional forcing of ideological shape into close-enough spaces (which we will politely ignore), but it can work. I’ve seen it work, among people who are wont to maintain community with diverse opinions. I went to Quaker school, ok?

The problem is that it sacrifices truth by too easily overlooking fallacy. Because it prioritizes the coherence of diverse ideas over the question of whether any of the ideas are rationally defensible in themselves, it cannot reliably lead to a picture of what is actually true or real. Rather than investigate each idea rationally and skeptically, the primary motivation is to fit everything together into a quasi-meaningful whole, which ends up distorted and full of many gaps and bulges where the pieces don’t quite fit.

This is why the skeptic, the new atheist, and the “realist” get such a bad rap around such harmonizing folks. They are working so hard to find ways to get us talking, agreeing, and peacefully co-existing that they are really not even concerned, and perhaps not fully aware of the relevance, of rational defensibility of ideas themselves. Such quibbling and nit-picking questions of such as us skeptics is annoying? Can’t we see that they are trying to paint a pretty picture? Why must we insist that it does not look like anything real?

We must be the kind of people that tell 3-year-olds that their picture of a pony looks more like, well, a crude circle and some randomly placed lines! This is not to imply comparison between 3-year-old children and defenders of social cooperation. Not at all….

And yet, so many people are so enamored with the cooperation of ideas, whether they be science v. religion or otherwise, that they don’t pay attention to whether the larger picture they are putting together contains pieces from more than one puzzle. They don’t pay attention to the fact that one might be labeled “reality” and the other “fantasy.”

They are blinded, or at least distracted, by the liberal mythology of cooperation and tolerance. They are biased by the mythological desire for social and interpersonal harmony. And then they rationalize it as if it were we skeptics and new atheists who are seeing it wrong; they often insist that we don’t understand what the picture is supposed to look like. They are distracted by the mythological goal, while we are asking questions about the many parts which don’t seem to fit.

The only way to be sure that the image we create will be coherent is to make sure that each piece is the right piece, from the puzzle of reality. We must each inspect our own ideas, as much as is practically feasible, to make sure that it is the right piece. If it does not fit with others’ pieces, then we have to inspect both of them to see where the problem may lay.

And if it turns out that the whole puzzle is not coherent, that the universe is not rational, then so be it. But so far it appears as if the many pieces fit together pretty nicely, so long as we are vetting ourselves–as well as others–before we place them down on the picture of human achievement.