Despite her penchant for fashion, she is among the best atheist speakers out there. This was awesome:

I have yet to met her, but I will hopefully get a chance to at some point.

Reason Rally, perhaps?

I’ll be there.

Despite her penchant for fashion, she is among the best atheist speakers out there. This was awesome:

I have yet to met her, but I will hopefully get a chance to at some point.

Reason Rally, perhaps?

I’ll be there.

Quick note: My blogging activity has been very light lately because I have just started working again. I am going to dedicate some more time to writing so that I can have at least a couple of posts a week, and hopefully more. One the positive side, my posts may become shorter (you’re welcome)

—

There continues to be conversations about the relationship between science and morality in the blogosphere (here’s some from yesterday), which is no surprise since it overlaps issues such as scientism, religion, and skepticism generally. These topics are all hot tamales, at least on my google reader.

Moral philosophy can bee thought of as an application of scientifically discovered facts to a problem in social dynamics. In a sense, it is a bit like a computer programming problem in that we know what kind of program we want to create (a harmonious society with minimal ill-treatment of its citizens), but we need to figure out how to achieve this goal with the software and hardware we have. The hardware and software are (loosely) ourselves, and the program we want to write involves coming up with a way to order social relationships in a way which benefits people while preventing their harm if possible.

And what is morality? Is it the study of how humans (or other sentient beings) interact in groups, or is it the study of the how those humans should act in groups given some given desires and goals? With morality the desires are given (they are the facts of our psyches), and the goals are at least defined even if not universally shared. It is the logistics of how to achieve those goals which are where science comes in.

Is this puzzle one for the scientific method, or more generally one for empirical research? That depend son how we are defining ‘science’ here. If it is meant merely are a set of tools towards pure research, where the empirical methodology we use is utilized in order to discover laws or support hypotheses towards some theory, then no. If it is meant as a more general application of reason and the scientific method, then yes. As I have written recently, I think that the term ‘science’ in terms of these philosophical questions (such as the issue of science v. religion) should make way for ‘skepticism’ instead.

Moral philosophy is not science in the same way that physics is a science. There is science where we know the road (method) but not the goal (like physics), and then there is science where we know the goal (some achievement, technological or otherwise) but not the path by which to get there. Morality is an example the latter; we know what we want to accomplish, but we need more information and analysis before we know how to get there. Morality is an applied science.

When we are talking about doing the science of morality, we are not talking about designing a set of experiments to discover the underlying laws of morality as we would with physics. But morality is a field where we have real, physical things about which we have questions and goals. We will use reason, empiricism, etc in doing moral philosophy but most importantly doing moral philosophy will compel the need for further empirical research, some of which might be physics. It will mostly be neuroscience.

So, to deny that morality is a scientific project only makes sense if we are to define science so narrowly as to limit it to pure research, rather than the larger skeptical project of discovering what is true or how to achieve things via naturalistic means. This is why I prefer to use ‘skepticism’ in place of science in so many conversations such as this, because so many people conflate ‘science’ with pure research. I think that is the source of much of the disagreement concerning this issue.

For people such as Sam Harris, Jerry Coyne, etc, ‘science’ seems to stand for that larger skeptical project. The best approach to any topic (including morality) is this skeptical method often referred to as ‘scientism’ by so many commentators, and confused with some kind of neo-positivism by others. That’s why morality is a skeptical project; it is by these empirical and logical methods that we can get real answers to meaningful questions asked.

For morality, the question asked is something like “how should we behave socially in order to allow people to maintain personal and social well being?” This goal of well being (or whatever term you prefer) is not the thing we are trying to determine or justify, it is the project of moral philosophy from the start. If we were not assuming, axiomatically, the values of well being, happiness, or whatever term we prefer, we would not be talking about morality at all, but something else. And what other method besides the empirical ones of science could we use to find out how to answer this question?

We are not using science to determine what morality is or should be, we are using it to find the best ways to solve the philosophical problem we are already aware of. That’s why this is not about the is-ought “fallacy.” We are not saying that these are the facts, and so we should do this. We are saying that here is the place we want to be, so how do we get there?

Much like how we are not using science to find or justify our desires for truth when we use it to determine what is true generally, we are not using science to discover or justify our desire for a moral society by trying to discover the best means to attain such a thing. If you don’t take that goal as axiomatic, then you don’t care about doing moral philosophy. Similarly, if you don’t care about the truth, you don’t do science.

We skeptical and scientistic moral philosophers take what the hard sciences give us through their pure research methods and apply it to this problem of creating a better society in which to live. That, to me, is applied science.

There have been quite a few comments in recent months—in articles, debates, etc—proposing the evils of scientism. Religion and science, say many thinkers, are compatible and to see otherwise is to see science’s reach as going beyond its fingers. John Haught, for example, defines scientism this way:

Sicentism may be defined as “the belief that science is the only reliable guide to truth.” Scientism, it must be emphasized, is by no means the same thing as science. For while science is a modest, reliable, and fruitful method of learning some important things about the universe, scientism is the assumption that science is the only appropriate way to arrive at the totality of truth. Scientism is a philosophical belief (strictly speaking an “epistemological” one) that enshrines science as the only completely trustworthy method of putting the human mind in touch with reality.

(Science and Religion: from conflict to conversation, page 16)

Now, John Haught is considered, by many, to be one of the world’s foremost experts in the relationship between science and religion. And while I don’t deny that he has a lot to say about both science and religion, much of it valuable, I agree with Jerry Coyne (as well as Eric MacDonald) that his fundamental views about the intersection of science and religion is problematic if not down-right absurd.

Part of the problem, as I see it, is that the critics of the so-called “scientistic” people (one is tempted to juts call them “scientists”) seem to not understand the position as it is commonly used by those, such as myself, who believe that science is the preeminent epistemological methodology in the world (perhaps the universe!). The other part is, as has been pointed out, that this method conflicts too much with theological methodology which is often non-empirical. People like Haught have a bias, a conviction that ties them to a set of doctrines which make claims at odds with science, and so they see something beyond the reach of empiricism.

But to say something is beyond empirical reach is to say that there are non-empirical things. Well, how would they know? How could they know? From where could they get that data? Revelation? By what train does the “revelator” travel in order to get from a non-material world to a material one? What are the connecting tracks made of? Without a justification for how they get their information, we are right to be skeptical.

And that’s precisely it, isn’t it? It isn’t about science per se, but skepticism. The critics of us scientistic people think that we are claiming that we can design laboratory experiments in order to find answers for all questions, even their magic ones. They think that when we say that science can answer questions about morality (for example), that we mean that people in lab coats can sit around with complicated bunson-burner experiments to determine what types of things to value, what meaning is, and how many angels can dance on the head of a pin. It is a rather silly caricature, isn’t it?

And that’s precisely it, isn’t it? It isn’t about science per se, but skepticism. The critics of us scientistic people think that we are claiming that we can design laboratory experiments in order to find answers for all questions, even their magic ones. They think that when we say that science can answer questions about morality (for example), that we mean that people in lab coats can sit around with complicated bunson-burner experiments to determine what types of things to value, what meaning is, and how many angels can dance on the head of a pin. It is a rather silly caricature, isn’t it?

If we are concerned with what is true, then we need to find tools which can help us find clues as well as shift through them to determine which of those clues can help. But further, we need to find the best tool-set to use, how to use them, and how to know when they are not working. Over the millennia human culture has developed a complicated history to how we determine the truth. From the early days of philosophy and rationalism through the enlightenment which brought us more powerful tools of empirical research, we have developed what we now refer to as the scientific method.

If we are concerned with what is true, then we need to find tools which can help us find clues as well as shift through them to determine which of those clues can help. But further, we need to find the best tool-set to use, how to use them, and how to know when they are not working. Over the millennia human culture has developed a complicated history to how we determine the truth. From the early days of philosophy and rationalism through the enlightenment which brought us more powerful tools of empirical research, we have developed what we now refer to as the scientific method.

It is through this method that we have the best information about what is likely to be true. No other methodology is close to competing in terms of practical success or theoretical power. This perpetually leaves me asking people who are critical of the scientific method what they could even try to put up against it. There is no competition. Cake or death, or something….

But despite this success of the scientific method, many people (especially postmodern philosophers and theologians) try and argue that neither empiricism and/or logic can tell us what is true. That is, we have to assume some axioms, we must assume some things, to get anywhere with any of these methods.

Well, of course we do. The question is whether A) other methodologies would have to accept the same axioms (such as non-contradiction, existence, and reliability of sensory perception) and B) whether this actually damages the method itself. All important questions, but also beyond the scope of this post. Instead, I want to take another related path here.

Do you value truth? Does it matter to you to have as many true beliefs as possible and as few false beliefs as possible?

As a preliminary, I must address the issue of whether I should have to justify why we should desire truth. Having to justify the desire for truth when considering what methodology to use in determining truth is akin to justifying hunger when considering nutritional value in deciding what meal to eat. If you aren’t ever hungry, there is no point in making such a decision. If you don’t value truth, there is no point in the consideration of methodologies.

Is it not a value of yours to know true things? If so, then just stop reading. Just go somewhere else, play some video games, and have a few drinks because nothing you say, do, or think is relevant any more concerning anything I have said here. If you don’t care about what is true, or if what you prefer to be true is more important than verification, then there is simply no talking with you about epistemology, methodology, etc because you don’t care enough so it does not matter.

If you do care, then it should be your value, as a direct logical descendant of that prior value of truth-having, to utilize the best methodology for determining if things are true. To accept any other method would be absurd, because it is not as good at determining if something is reasonable to accept as true.

And the best methodology for determining truth is, well, science right? Well, partially. The best methodology is actually…

That is, after all, the central theme of this blog. “The Atheist, Polyamorous, Skeptic,” right? The first two terms in that title are qualifiers of the last; they tell you what kind of skeptic I am. But further, I believe that skepticism, properly applied, necessarily leads to atheism (and possibly polyamory; a topic for another day), but that is beside the point that I am a skeptic first, which should imply that if the evidence were to point elsewhere I would be otherwise. Because evidence is what matters.

One of the primary ideas in skepticism is the idea of the null hypothesis. Now, I realize that in every day practical science this ideal is not a reality, but a s a rule of scientific inquiry in general it is essential as a part of the philosophy of science. It basically says that you should wait for sufficient evidence before accepting a hypothesis as true. That is, you withhold belief until enough evidence, or at least rational justification, is given to accept something as having a basis in reality.

Obviously the amount of evidence necessary to accept a claim is proportional to the claim; I don’t expect you to withhold belief in the claim that I ate pizza for dinner tonight; it’s not an extraordinary a claim that is worthy of serious skepticism, and accepting it even if false has little to no consequences generally. A supernatural being who created and controls aspects of the universe is a different matter, one worthy of skepticism and requiring good support to accept. As far as I have seen, no good support exists for such a claim.

Skepticism involves many tools and ideals beyond crude empiricism. Empirical testing, verification through demonstration of material effect, logic, reproducibility, etc. It is a large tool set which together give us a very powerful detection apparatus for what is true, what exists, and what is not sufficiently verified to rationally accept.

It is this method, that of skeptical inquiry, which the scientistic people are on about. It is not science per se but the whole set of empirical and logical tools which I call skepticism. It is thus my proposition that rather than call us “scientistic,” we should just call ourselves skeptics and have done with it. Rather than argue against scientism in the science/religion debates, we should be framing the debate as one about skepticism versus non-skepticism.

It is my contention that many fans of NOMA or other angles on the science/religion compatibility side are being non-skeptical, or at least not properly applying skepticism to all aspects of their beliefs, worldviews, or reality. I think this has been the crux of the issue all-along.

Against skepticsm, religion has a hell of a time competing. This is not to say that religion does not use logic, empiricism, or skepticism at all. It just often subverts them under the wing of revelation, authority, tradition, etc. Many theologians (including William Lane Craig) have said that if it came down to what science says and what their scripture says, they stick with scripture.

But of course many other religious thinkers, such as John Haught and Francis Collins, believe that the methods of science (and perhaps of skepticism) are compatible with their religion. But the problem with this is immediate, at least to me; religion is often essentially reliant on certain unquestioned propositions (sometimes referred to as “facts”) such as the crucifixion, the miracles of this or that deity or holy person, or the existence of a deity in the first place. These questions, when pressed against the methods of skepticism (and not merely science), do not stand. It has been one of the themes of this and many other “new atheist” blogs to demonstrate this week after week.

But when we open our skeptical tool boxes in the presence of ideas accepted due to tradition, faith, or unsupported personal experience we are told that those tools cannot reach there. We are told that the substance of those things, the nature of their meaning, or even there very ontological status is beyond material manipulation.

But we, as animals with material nervous systems which make up all that we are, are not exceptions to the universe. We ar enot privy to some magical bridge to some supernatural world. This has to be supported first. Haught and his cohorts on sciency-religious love-fests have to demonstrate that there is anything to their revelatory experiences in the first place. They have to demonstrate that there is any reason to accept that there really is a separation of nature from supernature before they start making claims that the questions about them need different tools.

Science and religion are incompatible because while they both deal with the real world, the extra stuff that religion is supposed to have exclusive access to are not credible in the first place. There is no reason to think they are real at all. Only the best set of truth-testing tools that we have can reliably determine what is likely to be true, and those tools don’t expose the presence of the magic world which religion claims propriety over.

If the science/religion discussion is about who can say what about what is beyond the scope of skeptical analysis, then I vote that we let religion have it. The result is that theologians get to play in imaginationland and skeptics and scientistics can go on having (as Haught says) “the only completely trustworthy method of putting the human mind in touch with reality.” What Haught and others don’t seem to get is that the rest simply is not rationally acceptable as real.

It has been asked of me, more than several times over the years, why I care so much about what people believe. Why can’t I just live and let live. Well, I do. It’s just that I don’t think that living and letting live necessarily involves not asking why people live the ways they do. I’m not stopping anyone from living by wondering why they live the way they do.

I have said it many times, but the truth is important to me. This is not to say I assume that all my beliefs are true, only that I try to believe things for good reasons. I try to have evidence, or at least good reason, for accepting ideas as true. So, if I do believe something I do think it’s true, but realize that I might be wrong and so I maintain an open mind about that possibility. This necessitates listening to criticism, going out of my way to challenge ideas (both mine and others’) in the face of dissenting opinions.

This skepticism of mine is part of my life project to be honest, open, and direct with the people around me. It is a value of mine to live authentically, which for me means that I don’t hide who I am to people, try not to allow self-delusion to survive within myself, and be open about my strengths and my faults. I challenge others because I challenge myself.

One implication of this is that I don’t want cognitive dissonance to exist within my mind, and don’t happily tolerate it in others. I don’t want to have ideas which are in methodological or philosophical opposition to one another, and I am sensitive to it in others. Cognitive coherence is a goal at which I will inevitably fail, but I strive for it nonetheless because to do otherwise is to capitulate to intellectual and emotional weakness.

Another implication is that I do not respect the idea that an opinion or view “works for me” as being sufficient to accept it as true. I actually care what is really true, not merely what coheres with my desires. This attitude is essential for a healthy skepticism. The desire to apply skeptical methodology to all facets of reality (sometimes referred to as “scientism”) is a value of mine, and I think it should be a value for everyone.

And this is why meeting someone who has little inclination towards this skepticism, who believes things which are not supported by evidence and do not care to challenge them, raises flags for me. It is, in fact, reason for me not to trust them.

Now, wait (you may be saying). How does being non-skeptical about things make a person untrustworthy?

Well, it does not make them completely untrustworthy. It would not necessarily mean that I could not trust them to watch my bag while I run into the bathroom or have them feed my cats while I’m out of town. No, it merely means that I will have trouble accepting some claims they make. It makes me trust them less intellectually.

They have already demonstrated that they are capable of being comfortable with cognitive dissonance, or at least in holding beliefs uncritically. They have demonstrated that they have less interest in holding true beliefs than holding comfortable ones. So if they were to claim some knowledge, opinion, etc I would be in my skeptical rights in having some issue with their trustworthiness.

This, of course, does not mean they are wrong. People with all sorts of strange ideas can be right about other things. It means that I would be more willing to demand argument or evidence for their claims, since they have already compromised their credibility in my eyes.

It also makes it harder to actually respect them, as people. It makes it less likely I will want to become closer to them personally. In potential romantic partners, unskeptical attitudes and beliefs are a turn off, for example. Beliefs in astrology, psychic powers, homeopathy, wicca, or even some aspects of yoga are indicators that a person may not be a new best friend or romantic partner.

Such beliefs are indicators that while we may get along well enough socially or in light conversation, our goals in life are incompatible. As a result, there is only so close I am willing to get because the attitude they take to the truth makes them vulnerable to deception. They have not exercised critical thinking to themselves or the world, and it seems likely that they may not know themselves well enough emotionally and/or intellectually and therefore are more likely to subject themselves, and thus people they are involved with, to undesirable situations.

This is not to say that people who believe these things cannot be educated or better informed, only that until they are willing to critically challenge such things they will occupy a place in my head of lesser reverence.

So, call be judgmental, elitist, and arrogant if you like. But I will judge unsupported ideas as flawed, consider demanding higher intellectual standards as preferable, and do not think that pride in these standards to be unwarranted. I am judgmental (so are you, so is everyone. I am just honest about it). I am elitist, and I don’t care if it offends your sensibilities. But arrogant? Well, I don’t think my ideas of self-importance, based upon my standards, are unwarranted. I think they help to make me a better person.

I’m honest, I care about what is true, and I hold myself up to high standards. If you don’t care about these things, then I likely don’t respect you. Live with it.

I’ve been having a long conversation in the comments of another wordpress blogger recently. I was perusing the religion section of wordpress and ran across this post. The comments are where it gets interesting. If you are interested in such conversations, I urge you to take a look. Much of the following will reference that discussion, although you will be able to follow without reading it).

During the conversation, which touches on skepticism and the definition of ‘atheist,’ the blogger jackhudson said that “there is no such thing as a ‘mere atheist’,” and I was forced to agree. Actually, I quite enthusiastically agreed, as I had never made such a claim that such a creature existed (see the comments there for the details, if you like). But I immediately liked the term and it gave me a little insight into the nature of our disagreement. It also reminded me of a discussion within the atheist community some time back.

Remember that now infamous PZ post about “dictionary atheists” with which many atheists, including myself disagreed? Well, I do believe that the definition of “atheist” is still merely the lack of belief in any gods, but I also agree with PZ’s larger point which, ironically, is basically the point that jackhudson is making in the comments I have made reference to in this post. Ironic because the post is about PZ Myers being wrong about something. Well, it’s a little ironic.

In other words, PZ Myers was right to say that we, as atheists, are not atheists because we lack a belief in gods. At the time he wrote that post, I disagreed by arguing, as did many pothers, that being an atheist was nothing more than this lack of belief in gods. But as I came to understand it, PZ had a larger view in mind, one which jackhudson is also making; none of us are merely lacking belief in gods. We have other things we do believe in and those things inform our worldview and tell us about how we are atheists.

Even if the definition of atheism is, in fact, the lack of belief in any gods we are so much more than that. It’s a nuanced point, and I think worthy of further exploration.

People come to find that they are atheists in a number of ways. As they do so, they carry all sorts of beliefs, assumptions, and worldviews (all of which may change, of course). But an essential moment for people who consider their beliefs is when they first realize that they no longer (or never did) believe in a god.

Some of these just of shrug their shoulders and go on with their life. Others experience a great emotional relief, anxiety, or even anger upon realizing this. I imagine that some people even repress this and go on as if they do still believe. The reaction is dependent upon many personal factors which are relevant to a person’s worldview, but are not really relevant to the term ‘atheist’ per se. That is, if they accept that title as part of their identity, that title merely tells others what they do not believe (gods), but nothing about what they do believe in.

Other labels and titles can do that, in most cases. Sometimes new labels have to be invented. But no information about what one believes can be gleaned, necessarily, from “I’m an atheist” by itself.

So, I think that PZ’s objection is more about the existence of “mere atheists” rather than “dictionary atheists” (although I’m sure he is still annoyed with people reminding everyone of this definition, as his post indicates). Having heard him talk about this issue a few times however, I don’t think he disagrees that atheism, per se, is merely this “dictionary” use, only that this lack of belief does not tell you anything anything about what is important.

And while I think it is still important to clarify one’s philosophical opinion (I am a philosophically-minded person, after all), I think that PZ is largely correct. I will continue to explain the definition when the clarification is warranted, but I think that this is becoming a secondary consideration for me. It is a bit of a transition I have been noticing for a little while; a bit of atheist maturing, perhaps.

At this point, my concern is to not argue what the definition of atheism is so much as to answer the question that Matt Dillahunty has become known to ask (What do you believe, and why do you believe it?) for my own skeptical views. That is, I am more interested in explaining my views rather than labeling them and having arguemnts which are purely about those labels.

It is true that I don’t believe in any gods. It is still true that to claim that no gods exist is beyond my epistemic powers. It is also true that in some cases (like with the Christian god) I do believe that ‘God’ is not real. But I think the fundamental point is to show that a skeptical position is where to start, and that I simply do not see reason to believe in people’s religious ideas.

My motivation for all of this is not derived from being an atheist, but rather from being a skeptic who cares about having beliefs which are true. My being an atheist is not my motivation for writing this blog, being active in godless communities, etc. My motivation is what I do believe.

I do believe that the truth matters. I do believe it’s important to want to have reasons for what we believe. I do believe that skepticism is the best methodology for finding what is true. I do believe that having a good level of certainty about truth is possible. I do believe that people can educate themselves towards freeing themselves from delusions of all kinds, including faith. I do believe that the efforts of the skeptical community are helping our culture move away from religious commitments, even if more slowly than many of us would like.

So no, I’m not a mere atheist, and I don’t think any person is. To be a person is to have beliefs, even if only tentatively, and nobody is defined by a simple lack of a belief.

But I still believe that identifying openly as a person who does lack that belief, in this cultural context, is important for the ongoing cultural conversation. I do think there will be a time when identifying as an atheist will no longer have a use (it will still be true, but only useful in the way that identifying as an a-Santa-ist is now).

We are not there yet.

So, remember several months back there was this whole big thing about the world ending on May 21st, 2011? I mean, there were billboards, people on the street handing out pamphlets ( I still have a copy around somewhere), and lots of media talk about it. In fact, I wrote about it here.

And then the date passed. Explanations were rationalized, and the world moved on. You see, a judgment occurred, but it was “an invisible judgement day”. The end of the world was still coming, it was just happening later…really. So when is that date again?

And then the date passed. Explanations were rationalized, and the world moved on. You see, a judgment occurred, but it was “an invisible judgement day”. The end of the world was still coming, it was just happening later…really. So when is that date again?

Oh right, it’s tomorrow.

That’s right folks, the world really is ending on October 21st, 2011! For real this time. I mean, Harold Camping can’t be wrong 3 times, right? Oh, that’s right…he made a similar prediction back in the ’90’s.

Well, in case this ends up being my last post ever (assuming I don’t post some attempt to repent as I see Jesus descending on a could or whatever), I hope you have all enjoyed the show.

But I am betting that life will go on tomorrow as usual.

[edit]

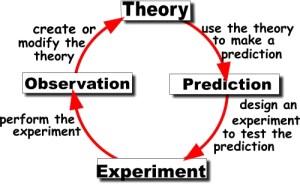

I love this image!

Yesterday I wrote up some comments about doubt and faith. I am quite happy with it as it stands, but a question was emailed to me from an acquaintance that led me to wonder if I had not been sufficiently clear about one thing, so I wanted to publicly clarify a related question.

The comment emailed to me was this:

Doubt is not the opposite of faith – fear is the

opposite of faith

It was followed by a question about whether there is a difference between religious faith and the belief in things that you simply don’t know for sure or don’t have evidence for (yet, due to lack of sufficient information, etc).

I responded thus (edited to exclude unnecessary specific information):

—

I have heard that comment about faith, and I don’t buy it. I think that the fact that you don’t know [some specific fact] and faith in supernatural things, or at least things for which there is no evidence, are very different questions.

I make a distinction between a reasonable expectation and faith. Based upon your limited experience with me, your understanding of human behavior, etc you can assign some rough probability to my potential actions. You have empirical information upon which to make a guess, even if your certainty about it is shaky. But if you have a belief in a thing that you truly cannot prove, or at least that you do not have evidence to support or rational reason to accept, that is a qualitatively different question epistemologically.

Also, I would be cautious in using the word “prove” or “proof.” In questions of empiricism, such as science, we don’t ever prove things. We gather information, create a hypothesis to explain the information we have, and if that hypothesis stands up to scrutiny then we call it a “theory” which is further tested and stands or falls upon that further testing. But we cannot deductively prove such things because that is only applicable to purely logical/mathematical questions; things that only exist in the abstract. Questions such as what will happen in the real world are not subject to formal logic, and so cannot be proved. There is always room for doubt, even if it is very small.

So, to accept something like “there is a god” or “a soul exists” despite the lack of supporting empirical evidence is faith because faith is the belief in something despite the lack of evidence (or in the face of conflicting evidence). To believe something that has not yet been given support (in this case because it is a proposition about the future) is a probabilistic process; you can assign probabilities based upon experience with similar situations. But since we have no evidence which supports certain types of claims (like a soul, for example), we cannot assign any probabilities because we have no supporting data to work with. A probability assigned in such a situation would be purely fictional and arbitrary.

In short, they are not the same thing.

Fear is not the opposite of faith because it is possible to be in a position of believing something that you have no evidence for because of fear or at least while experiencing fear. Not that it must be the case, but that it is not logically incoherent. Therefore, they cannot be logically opposed. While doubt (the state of recognizing uncertainty about some question) is not the opposite of faith, is not easily consistent with it. My claim is not that doubt and faith are always incompatible or opposed, only that faith often does not long survive in the presence of doubt.

To truly doubt something means that the belief becomes mitigated. To be a skeptic (which includes doubt but is more than that) is the opposite of faith. Skeptics only believe a thing based upon evidence or reason. I am a skeptic first, and that leads necessarily to atheism and the lack of belief in many other spiritual or religious things (because of the lack of supporting evidence). Until supporting evidence is presented, this is the only rational conclusion for a skeptic. Someone who does not care about evidence to support their belief is not concerned with rational conclusions, so asking what would be rational in that case would be irrelevant.

I care what is true, and want to have as many true beliefs as possible. As a reuslt of this, I doubt things for which there is spurious or no evidence (often to the point of lacking belief in them). I still may believe untrue things, and am open to being shown that this is the case. I have not found this attitude to be true for many religious or spiritual people, although there are obviously many other exceptions to this observation.

I hope that clarifies my views on this.

I have been told by many people, over many years, that doubt is part of faith. The idea is that a person who does not challenge their faith has a weak form of faith. I sort of appreciate the sentiment here, but I wonder how genuine this is. I wonder how deep this lauding of doubt goes. I wonder if it is real, skeptical, doubt.

Skepticism is about doubt. A skeptic is a person who demands substantial evidence in order to accept something as true. Yes, a person may not be ideally skeptical about everything, and therefore may accept as true beliefs which would not stand up to even their own scrutiny if they were to apply it. But I think this is simply the nature of our cognitive limitations. In other words, we are all credulous to certain dumb beliefs, but we’re just human.

It take a certain amount of courage to dig deep into your own beliefs. To be an archaeologist of the soul, as Nietzsche put it, is a hard task. And not everyone will be up for it, nor would most know how if they tried; we sometimes need a little help from our friends, I suppose. And so when I meet a religious person who has the courage to at least make a surface or moderate attempt to doubt, to dig beneath the surface of their convictions, I find myself bestowing respect upon them, at least provisionally.

The provisional nature of this reverence is necessary, I have learned, because the institutions of religion, the insistence of doctrine, and the fragility of faith’s foundations are such that such ego-archaeological excavations often lead to one falling into holes, and thus clutching onto the ground of such landscapes in order not to feel the true exhilaration of freethought. To fall into oneself, underneath the facades of our social selves padded with commitments to supernatural hopes, is a terrifying prospect in the face of oblivious alternatives. The human condition of being, in the end, alone and finite (it’s alright) is a reality which doubts lead to, and which is less often the object of faith.

How often have you met a person committed to a faith that they will cease to exist upon death, and that there is no god that loves them? These ideas are conclusions reached upon careful thought and skepticism, not hope and desires. The claim that these ideas are equally based upon faith are absurd, and are an attempt to level the playing field. It is a rhetorical trick with no substance. Faith seems to almost exclusively own subjects which we seem to prefer (like Heaven), or at least fear as an alternate to what we prefer (Hell).

So, does this imply that faith and doubt are truly at odds? The snark-laiden answer is to point out that if people had evidence (the answer to doubt), then they would not need faith. And while I think that this snark contains an important insight into the nature of the question of faith and doubt, I think that we can go elsewhere to address this issue. The skeptical methods, science and reason, are a means to figure out what is likely to be true given our best tools for determining such things. Doubt, in other words, is the seed of science and all of our (limited) mastery of the natural world. Faith seems to be opposed to this progressive methodology, both philosophically and practically. Anyone who has a long conversation with a true believer will ultimately hear the faith card played; all of our questions, doubts, and debunking of theological apologetics runs into this wall at some point.

Recently Eric MacDonald weighed in on this question of doubt and faith with the following, which was a concluding comment to his long piece about a Julian Baggini article in The Guardian:

If the kind of questioning ”theology” that [Richard] Holloway now indulges in were to become the norm, the churches would simply fly apart from the centrifugal forces of doubt and questioning. And that is why religion will remain dogmatic at its core, and why openness to changing one’s mind is simply not accessible to the religions. It may happen one by one, as religious believers are leached away from religion by the corrosive forces of science and reason, but a religion whose leaders were open to changing their minds in the way that [Julian] Baggini suggests is necessary in order to avoid fundamentalism would spell the end of religion, because religions have no foundation. They are built on air, and openness to revision would quickly expose this.

That is, even where doubt, or questioning in general, is encouraged (whether by accommodating atheists or moderate or liberal theologians), it is a recipe for the excavation of holes in the landscape of religion and the faith which binds people to it. Doubt may be considered a part of being a faithful person, but the religion that survives this process is not the same as the religion that was handed to us from pre-scientific ages. This religion is moderated by compromise, non-literalism, etc and away from fundamentalism. Eventually, it erodes away into postmodernism, metaphors, and empty vessels with sentimental import.

And this is precisely what religious academics, such as the Bishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams and King’s College president Dinesh D’Souza have been doing for some time; we “new atheists” are addressing a straw man, they say, and religion is full of doubt, questions, and nuance which are ignored by comments like Eric MacDonald above. For such people of faith, doubt is part of their lives and to imply that faith is somehow antithetical to doubt is to be unfair and biased in a way that does no justice to sophisticated theology. But it all falls apart, at some point. Eventually, in the corrosive environment of doubt, religion becomes a shade in tattered robes that haunts our ivory towers and sanctuaries, largely unseen by the masses whom insist upon feeding on the corpse of literal truth, real historical promises, and miracles.

Well, Eric MacDonald (who is no stranger to sophisticated theology), Jerry Coyne, and others have said a lot about this very subject, and I shall not try and sum up their thoughts on such things here, as this would quickly turn into a small ebook if I were to do so. So what I want to do is pose some questions which I intend to follow up on in the future. They are questions about faith which I have some perspective on already, especially in conversation with former Christians (almost exclusively) about the role of questions and doubts in religious communities. Having known people who would pose tough questions, voice doubts occasionally, etc within their religious communities, I have seen how some moderate religious communities (like Tenth Presbyterian in Philadelphia, where I visited a couple of years ago) respond to such things. Doubt and questions are not met with curiosity or answers, they are often met with ostracism and loss of friends, as I have had it explained to me. Also, in my experience, outsider’s questions and doubts are treated with initial interest and then silence, in the vast majority of cases.

My questions are as follows (and I intend to ask them of people in positions of leadership in religious communities in coming months):

As I said above, I have some experience with exposing religious ideas to doubt. In the extremely vast majority of cases (I have not maintained a running count, but there are few exceptions) even when questions, responses, or criticisms are proposed, they almost always fizzle into nothing. It is almost as if the leaders of these communities, whether they are priests, pastors, or whatever are so glad to hear some commentary, feedback, etc that they  don’t notice at first that you have some serious objections to the message they are conveying, and then once that sinks in, they simply close off. They are not interested any longer. I suppose I am not surprised, nor should I be.

don’t notice at first that you have some serious objections to the message they are conveying, and then once that sinks in, they simply close off. They are not interested any longer. I suppose I am not surprised, nor should I be.

But right now, from where I sit, true skepticism, the kind of doubt which seeks to excavate the very foundations and assumptions of one’s worldview are not healthy for faith. But perhaps I err in using “faith” as the Christian scriptures do:

Now faith is confidence in what we hope for and assurance about what we do not see.

Because that seems, on the surface, to be in philosophical opposition to skepticism, and therefore to doubt. Perhaps some other religious tradition has a use of the word faith which differs from this. I don’t remember much about what the Quran says about faith (there is this, for starters), but I doubt that it says much that is friendly to skepticism. And insofar as many religious people do have and maintain doubts, how far do they push those questions, are their questions they would refuse to apply doubt to, and would they truly be open to changing their mind?

I have long said that I want to know the truth. If there is a god (or gods) I want to know. I am open to being convinced of things which I do not currently believe. Do believers share this quality? And if so, how many and to what degree?

And why aren’t more people doubting?

What possible misdeed could finally push people away from this monster?

I mean, a plethora of examples of sexual abuse of children in the last several years have not driven them all away. There are also the less media-fun indulgences which have come back from the dead of pre-Enlightenment days. There is the problem of condoms and the subsequent HIV problem in Africa and elsewhere. Also, there is the fact that there simply is no evidence for their ridiculous theological claims. But that’s not really morally awful so much as it is epistemologically tragic.

But then again, at least the Catholic Church has not been responsible for child-theft and trafficking, right? I mean, maybe one or two Catholics have done such a thing, but at least it has not been a systematic and decades-long problem involving hundreds of children.

Nope. It’s apparently been hundreds of thousands of children for 50 years.

Up to 300,000 Spanish babies were stolen from their parents and sold for adoption over a period of five decades, a new investigation reveals.

The children were trafficked by a secret network of doctors, nurses, priests and nuns in a widespread practice that began during General Franco’s dictatorship and continued until the early Nineties.

Hundreds of families who had babies taken from Spanish hospitals are now battling for an official government investigation into the scandal.

Several mothers say they were told their first-born children had died during or soon after they gave birth.

Disgusting. Beyond disgusting. If you are still a Catholic, you have some serious explaining to do. I cannot fathom an excuse sufficient to satisfy me here, but by all means try. I question your moral compass if you ever walk into a Catholic Church for anything except escaping the zombie apocalypse. OK, I might accept attending someone else’s wedding, or possibly in order to simply look at the architecture of many beautiful cathedrals, but there is no excuse for attending a Mass and giving any money to the church anymore.

You’ve long-ago ran out of excuses.