A little while back, I wrote an article about my experience in visiting a Presbyterian church. I contacted the gentleman who gave that sermon that day, exchanged a few pleasantries, but never heard from him again after he read the article. But I am not dissuaded! I press on, and I visit other churches in the hope of maintaining some communication between people like myself and those with whom I share little in terms of metaphysical opinion.

But, as I discovered yesterday (Sunday, October 25th, 2009), I do have a fair amount in common in other areas besides my theological persuasion. Yes, I might say that I found that I can agree quite closely with a worldview expressed at certain churches on certain days. And with that, allow me to report what I found at a local Vinyard church yesterday…

—

A gathering of young, attractive, and slightly swaying people gathers under the chord-changes that seek to immitate the presence of a holy spirit. Some sing along in praising the resurrection that supposedly brings them joy and peace. One, standing before them, prays for all those who, assuredly still attached to the unseen powers of the real world, arrive late. As they sit, a prayer of fear is offered. It is that which should be learned; fear. But wait, there’s more! See, God will come to the down-trodden and those in need. No doubt pain, loss, and fear are felt here. No doubt they come to this place with this need.

One day, every knee will bow

one day, every tongue will confess

they sing. An insecurity sits in this song which hovers over the crowd like a mist, almost visible it is so strong. A vindication of their faith lives in these words. Their belief is justified by that promise this time of all bowing and confessing which cannot verified, but its hope is palpable here. Their swaying continues with the new song. Hope, genuine affection, a few hands raised as if to catch something unseen but certainly felt. The evidence of things unseen? Perhaps.

Then they sit. I have been sitting and jotting my impressions. This has earned me some attention. They seem to wonder what I am writing, and perhaps why I am writing. Perhaps they wonder why I am not moved by the spirit as they are. Perhaps I project. Perhaps they are just not used to seeing this particular action in this particular place and time.

God comes close to us when we grieve

starts the pastor. He talks of loss. There are those that are no longer with us. We must set aside time and space to grieve for those who are gone. Do not be satisfied with the thought that they are in a better place. Well said. But well said for different reasons than the ones I might give.

And this would be the theme for me throughout the next hour. I, the atheist in the pew, will find myself in agreement with much of what is said in this sermon, but will wonder a recurring question throughout;

What does this have to do with any god?

The inspiration, as it were, for this sermon is Matthew 6: 25-33. For those of you who don’t remember, it is the section where Jesus instructs us (supposedly) to “look at the birds of the air” and to “consider the lilies of the field.” In fact, I’ll just quote the section that the sermon was derived from (NRSV):

‘Therefore I tell you, do not worry about your life, what you will eat or what you will drink,* or about your body, what you will wear. Is not life more than food, and the body more than clothing? 26Look at the birds of the air; they neither sow nor reap nor gather into barns, and yet your heavenly Father feeds them. Are you not of more value than they? 27And can any of you by worrying add a single hour to your span of life?* 28And why do you worry about clothing? Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow; they neither toil nor spin, 29yet I tell you, even Solomon in all his glory was not clothed like one of these. 30But if God so clothes the grass of the field, which is alive today and tomorrow is thrown into the oven, will he not much more clothe you—you of little faith? 31Therefore do not worry, saying, “What will we eat?” or “What will we drink?” or “What will we wear?” 32For it is the Gentiles who strive for all these things; and indeed your heavenly Father knows that you need all these things. 33But strive first for the kingdom of God* and his* righteousness, and all these things will be given to you as well.

This is a section that I am well aware of. I remember a British sketch comedy bit about it that I found funny (I could not locate it to embed–sorry. If you know of it email me a link). I will tell you that I think that this passage is plagued with some problems, and as soon as the pastor began his discussion I wrote them down immediately.

But don’t the birds have to work for their food and shelter? The ones that could not died out and the ones that could are still here, so how is this supposed to be an inspirational analogy? Quite simply, I think Jesus is wrong here, and frankly looks quite ignorant of the life of birds and lilies.

The problem is that the passage states that the birds and lilies are taken care of. The idea is that in a similar way, god takes care of us. We should not become anxious over our lives because God will take care of things. We need, says our fearless pastor, strive for peace and simplicity.

Simple enough, right? See, it isn’t up to us. “We think that we are in charge,” but in fact God is in charge. God wants us to buy into a discipline of not worrying so much; to live a life of simplicity. We are complex, but Jesus preached simplicity. And in this materialist culture where one can get distracted by gadgetry and so forth, we should live by some basic guidelines to simplify our lives.

In a world of competition, we need to avoid the temptations of power in an attempt to maintain a life of integrity and value.

OK, I’m with him so far, mostly. So what does this have to do with God? What does this have to do with Christianity? I’m with you, my friend, but just because this idea was drawn from a passage from the New Testament, does that make this message a Christian one? Because as you continue to speak, dear pastor, the more I am reminded of Epicurus.

But there is more. You see, children buy into things easier.

…

Richard Dawkins is shitting himself…but in a dignified, British way…

I’m being a little unfair, I suppose. The idea is that we should try and maintain a child-like approach to learning and truth. We should remain open-minded and receptive. Perhaps, but not so open-minded that our brains fall out. In my opinion we need to remain open yet skeptical. Children are not always so skeptical. They tend to believe what you tell them because they need to be so open in order to learn and to survive. Had it been otherwise, those children thousands of years ago who didn’t believe their parents that the tiger didn’t want to be petted would not have survived and that particular trait of needing to verify everything they are told as a child would not have been passed down to the next generation. Simple natural selection.

Child-like, indeed. It allows the theology to be swallowed easier if we don’t ask too many questions. Child-like adults all gathered here listen intently, a few subtle motions and grunts of agreement can be pulled out of the quiet congregation.

I was partially with the pastor at this point. I thought there was some value to the idea to not try and control everything and to try and simplify our lives. I do not agree that we are not in charge and that God is, only that while we are in charge, there is no point in trying to control everything and to take a step back sometimes. This will help with anxiety, I agree. I strongly disagree with the idea that the responsibility is in a god’s hands. I think this is antithetical to our responsibility, and it seeks to have people not take pride in their accomplishments or to take responsibility for their mistakes. I do not believe the pastor would agree that this idea promotes irresponsibility, but this is precisely what the logical conclusion of this line of thought leads to, in my opinion.

But then he made a comment that stuck out to me even more. “Because we lack a divine center, we seek materialism” (or something very similar to that statement). This is the point where he lost me completely. See, I’ve never been a man of any god. I’ve never believed in Jesus, Allah, or any of those silly things, and yet I am in almost complete agreement with his essential message that he will deal with in the next section of his sermon.

He then discusses our insecurity (irony?) We seek answers, community, etc and sometimes we reach in the wrong direction in life. Amen, brother! But what does this have to do with God? Oh, right…without a divine center (that is, without God) we don’t have a goal-post to strive for. We don’t have s source of wisdom with which to make better decisions in our lives. Thus the following pieces of advice are really based upon God.

There is a terse reply to such a claim; fucking bullshit.

I call bull on this because I know that I, who have never been a Christian and don’t believe in any gods, agree with the rest of the sermon (mostly). I have come up with and learned the same pieces of wisdom from secular philosophers (such as the previously mentioned Epicurus), and many of them pre-date the Bible or are from non-Christian sources. These are not Christian pearls, they are usurped wisdom taken from the real world and illegitimately associated with Jesus for Christians, partially in order to feel special and different in comparison with a materialistic amd power-driven world.

Then, there was a list of ten pieces of advice that was derived from a man whose name seemed familiar but that I could not place at the time; Richard Foster. And the more the pastor went on and on, the more I kept thinking ‘this reminds me so much of my Quaker school and the stuff they talked about’ and thinking that this guy, this Foster, was ripping stuff off from the Quakers. And then I remembered (later) that Foster was a Quaker theologian. And I laughed. I had simply found yet another liberal Christian church who had a message that was just like the one I had grown up with. But I had never been a Christian. I had just attended a Quaker school. And the Quaker school I went to was dominated by Jews as much as Christians.

But I had learned these ideas not in relation to a god necessarily, but as good rules to live by in society. These are liberal ideas which can also be found in the Bible (although perhaps not for some), although they are not the only messages contained therein.

Again, what does this have to do with god?

Nothing. Nothing at all. All of this God-talk is merely a metaphor (an excellent article, so read it) for these ideas to live by. These things would be true whether or not thereis a god. God is being given the credit for this wisdom just because a passage in Matthew happens to touch on the issue, and only sort of. A better source for this discussion may have been Ecclesiastes, in my opinion. But this is what pastors do; they take a passage and associated with some cultural message and give the credit to their concept of god rather than to themselves.

The bottom line here is that in churches like these where God is talked about but only in ignoring the nasty stuff he has done according to that book, what is being preached is just sense. It should be common sense (and perhaps it is) but as I watched people react to the sermon, I saw them inspired and in love with this concept of god not realizing that they are giving this god the credit rather than taking it themselves.

We are not the ones in charge, he had said. God deserves the credit. I disagree as strongly as I can disagree with anything. This is a disgusting and anti-human message. It de-values us by making us puppets for a megalomaniacal bully (seriously, read the whole book some time). It seeks to humble us in a way that not only does not cure the insecurity within us, but perpetuates it. It is a slave morality, as Nietzsche called it. It is a way to keep people down under the guise of worship.

And what’s worse is that they don’t realize it. They don’t see that this message of allowing God to ‘take the wheel’ (as that awful song said) can take away anxiety, sure, but it also takes away the joy of accomplishment, the pride of success (it is not a sin to be proud–what kind of sick and twisted view would claim that out loud and call itself moral?), and the responsibility that we have for the world around us and within us because it takes away the credit of our effort. It’s all gone to the glory of God. That’s disgusting!

Do I sound angry? Well, I am a little. I am angry that people go to these churches to receive mediocre advice that can be found in any number of places without having to prop up a belief in a god for which there is no evidence. Further, these efforts continues to give credit for this mediocre wisdom to this imaginary being and circularly gives ‘evidence‘ for that god by actually sounding like it makes sense. After all, things that make sense can only come from God, if you assume that God is the source of all wisdom. Gotta love circular logic.

The bottom line is that I had a chance to hear a sermon that I agreed with a fair amount, but I didn’t see any reason to believe that it had anything to do with a god. Modern liberal Christianity still seems to me to be nothing more than a group of young and progressive people who like hearing nice things, especially things that challenge the consumerist and materialistic capitialistic world they live in, and then attributing the ideas to Jesus who will take away their pain and let them live forever. I wonder if they have really contemplated eternity. That’s a scary concept. But Jesus is magic, so he’ll take away that scariness too, I guess.

At least they aren’t Pagans; man, they annoy the crap out of me.

Atheists are distrusted more than any other group in the United States according to at least

Atheists are distrusted more than any other group in the United States according to at least

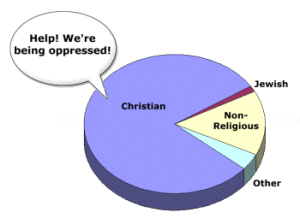

It is clearly true that most people believe in god and that, in the end, we should at least try to choose one life-partner. Not everyone will like that term, conservatively preferring the more traditional ‘husband’ or ‘wife,’ but this seems to be the prevailing assumption among people in our culture.

It is clearly true that most people believe in god and that, in the end, we should at least try to choose one life-partner. Not everyone will like that term, conservatively preferring the more traditional ‘husband’ or ‘wife,’ but this seems to be the prevailing assumption among people in our culture.

One of the charges leveled against the so-called “new atheists” is that of arrogance. This comes in more than one form, however. The first can be exemplified by the recent book

One of the charges leveled against the so-called “new atheists” is that of arrogance. This comes in more than one form, however. The first can be exemplified by the recent book