This is a continuation of a series of quotations from, and commentary of, my reading of John Frame’s book, Salvation Belongs to the Lord, which I am reading for a class about faith in Christian life. I will be under-cover, so shhhhh…..

—

So, what shall we speak of today?

The Trinity.

Oh, joy! That’s an easy one that can be covered in a blog post, right? Well, no. I would just like to quote Frame from the chapter entitled God, Three in One and makes a few observations.

Remember, though, that Scripture gives us only a glimpse, not a treatise…. Much that the Bible teaches about the Trinity is very mysterious, and we must bow in humility as we enter into this holy realm

(page 30)

So, in other words the Bible is vague about this doctrine, but we are going to humble ourselves before it anyway? OK, I thought that the Bible was the ultimate source of truth, and so where it is vague we will simply humble ourselves to a view that was attained through latter interpretation of vague verses? I’m getting ahead of myself….

Frame then lists 5 assertions (his term), which I will simplify into a list.

- God is One

- God is Three

- The three persons are all each fully God

- Each person is distinct from each-other

- They are related eternally as Father, Son, Holy Spirit

Ok, let’s start with #1. I don’t believe it, but I understand. How about #2? I don’t believe it but I understand…that is until my memory reminds me that #1 said something which flatly contradicts #2.

So, after I pick up the pieces of my exploded brain, I take a deep breath and try to move onto #3. I can’t. My brain is still experiencing some sort of stop error, and I cannot move on. The first two assertions are purely contradictory. But this is supposed to be a mystery. And besides, my mind, intellect, etc are fallen, sinful, and broken. I am not supposed to understand, but just accept.

Except that the Bible is vague on this point….

*sigh*

Let’s move on. Frame says that there have been “debates over the deity of Christ.” Not just in modern times, but in ancient times. During the 3rd and 4th centuries, many views of Jesus conflicted among the early Christians, even though Frame does say later (in chapter 10 entitled Who is Jesus Christ?) that there is no debate in the NT about this issue. One wonders how now-heretical views could have formed without Scriptural basis? Probably it has something to do with the fact that the canonical books that became the Bible had not been declared canon until after 325 AD. Before then there were other texts being considered as authoritative by many people. Many of these books are gone, some have been subsequently found.

Still, continues Frame,

But the conclusion of the Christian church since its inception, and the conclusion of the Bible itself, is that Father, Son, and Spirit are each fully God.

(page 32)

Sure, the Bible as voted one by councils in the 4th century (starting with Nicaea). The letters, gospels, etc that created a theological problem for this view were considered heretical, and often destroyed. So, while the scriptures that became canonical were vague at best, other writings made this issue even less clear when considered. Modern readers often do not know about these non-canonical texts, and so they are out of mind. Still the Bible we have is vague about this doctrine, but this idea is central to most Christian theology almost without question.

Yeah, that makes sense….

Frame adds this;

The work of theology is not just reading through the Scriptures but applying the Scriptures to the questions people ask, applying it to their needs.

(page 35)

Seems innocuous enough. Then you start to think about it. Theology is an attempt to categorize what is written. It is an attempt to make sense out of the Scripture in terms of what matters to us in our lives, right? Why would the Trinity be necessary for this?

Let’s follow the trail and see where Frame leads us. At the end of the chapter, Frame tells us that

If Jesus the Son of God is only a creature, [Athanasius] said, then we are guilty of idolatry….[Jesus] is worthy of worship only if he is equal to the Father….”

and then further down the page,

If the Arians were right…then we are hoping to be saved from sin through a mere creature. Only if Jesus is fully God, a member of the ontological Trinity, can he save us from our sins.

(page 41)

Ah! I see now. The Trinity becomes a doctrine to explain how Jesus, his so-called sacrifice, is able to have theological import. The Trinity is a solution to a problem of getting to where theologians want to get; salvation. It’s a puzzle-solution, not a philosophical methodology for figuring out what is true, lines up with reality, or anything like that. (Heresy!).

If you read the New Testament, you will not find a clear treatise on the Trinity. Jesus does not say he is equal to the Father and the Spirit, that they are all 3 persons of the same substance, or anything like that.

But Jesus is supposed to have said something things that would have been heretical to the Jewish establishment and which identified him as at least similar to God. The whole “Son of Man” thing, the doing of miracles, etc. So, by taking these puzzle pieces and structuring them into the Trinitarian formula, Athanasius and the early church along with him put together a coherent whole that, while not sensible, seeks to harmonize the claims of the gospels, Paul’s writings, etc. It’s a matter of creating the appearance of coherence in God’s Word, not in making sense of reality based on logic, rational enquiry, or (gods! no!) any proto-scientific method.

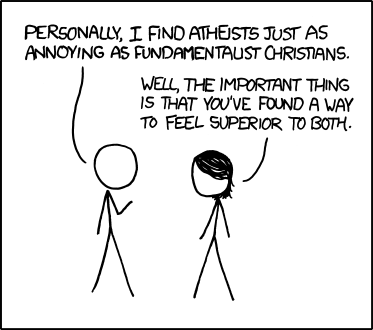

This seems to me to be a strange, backwards, way to figure out a mystery. Philosophical methodology might ask you to figure out what is logically possible then try to apply that to what is found. Here, logical possibility is thrown out as a criteria because we are broken, body and mind. The Word is the authority, our minds are broken.

We cannot trust ourselves, our minds, or rational thought.

Well, all there is to do under those conditions is believe, right?

Ugh….

Don’t think about that too hard.